Technical climbing: slabs vs. overhangs

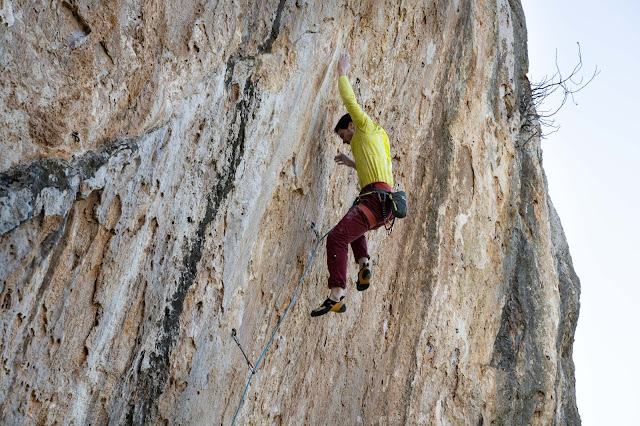

How often can we see a top climber explaining a route they are working on with something that goes along this line: "the headwall is not that hard, but it's technical climbing". They spent several sessions polishing the heel hooks, the toe hooks, the timing of dynamic moves, the nuances of generating momentum on the meat of this overhanging beast. They did the final slab second go. It had three bad footholds and a weird crossover move on sharp crimps, but this is the technical climbing, not the overhanging part. I just don't get the logic here. A sketchy slab and a straightforward overhang. Or the other way around? Photos by Sophie Grieve-Williams and Hu Chen on Unsplash . To be honest, sometimes I'm not sure what people mean by technical climbing. There are so many different techniques, is it like anything but ladder climbing? It's even used in contradictory contexts, some people say "it's technical" when it's easy climbing, others wh...