Tying in after a break

Fear is a natural part of our sport, because climbing is inherently dangerous. We can mitigate the consequences of a fall by using proper equipment, like rope in sport climbing or crash pads in bouldering, but we can not remove heights from the equation, because this sport is about scaling them. And a fall from height can be fatal, hence the consequences of an accident are most of the time very serious. The overall probability of an injury, however, is much smaller than in many other sports or activities. Climbing can be objectively safer than driving a car, if you do everything by the book, nevertheless the small but real possibility of falling to your death or seriously injuring yourself stimulates the imagination. Humans did not evolve to feel comfortable at heights, but as with most of fears it can be alleviated. We surely didn't evolve to feel comfortable moving 120 km/h in a metal can, but after years of doing it most of us don't even think about potential consequences of a car accident. When driving a car and when climbing, it's the equipment that makes us safe. Should something fail at 120 km/h we are likely dead, similarly to falling from 20 m. But somehow the speed has much less respect among people than the height.

The strange part is that one can be 100% sure that a climb is safe, after a rational analysis on the ground, and still feel anxious or even panic on the wall. Of course, it's hard to be completely sure, you can always sprain your ankle or hit your knee, but if you know the route, you've climbed it before, it's popular in the area so there is no loose rock, the bolts are bombproof, no rockfall from above, you have appropriate gear in good condition and a skilled belayer, you did the partner check, and you are all sober - then sport climbing is as safe as hiking. And even in such situation climbers can stress out when feeling some space below their feet and start thinking whether that quickdraw (which looked completely fine on the ground) is going to stop a potential fall.

|

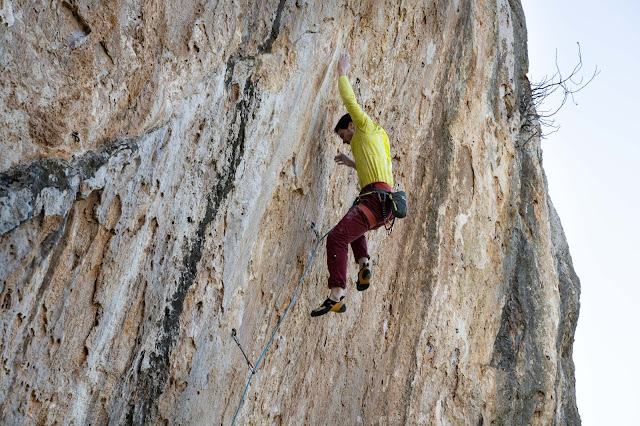

| One of my most memorable routes, Sarcófago 7c. On the redpoint tries I had to skip the quickdraw at my knee making the ride down quite long. Becoming comfortable with it was a crucial part of the successful send. Photo by Amanda Kowalski. |

It seems that all the conscious effort to make climbing as safe as possible does not eliminate the irrational fear of falling. I get a harsh reminder about that fact each time I go back to sport climbing after a break and ever since I started climbing seriously (full-time hobby seriously) other things in my life dictate prolonged periods without lead climbing. I still train indoors or do bouldering, but it does nothing for the mental game on a lead, hence I need to retrain my head every time I get back at it. Granted, each time it is easier and they say that eventually, after 20 years of climbing or so, you don't loose it, but I am not one of those lucky bastards with amygdala malfunction who just goes for it. Or maybe that's why I haven't had any accident so far. Either way, I am one of the people who need to push themselves to do bold things, because I naturally lean towards redundant safety checks. However, there are climbers who are exactly the other way around and would benefit from slowing down a little bit if they are planning a lifelong career.

I climb for fun

Once we made sure we are safe to go, the irrational (however natural) fear of falling is nothing more than an obstacle. It impedes our ability to climb, makes it impossible to push our physical limit, worsens our decision-making (think putting fingers in bolts or garbing the "hot" end of the rope when falling), and most importantly takes away the joy of climbing. Whatever goal you have, whatever your motivation for doing this sport is, uncontrolled fear and anxiety will inevitably damage your experience. Personally, I like climbing hard, I enjoy the training grind, the relentless search for the optimal beta, and never-ending improving on the individual moves of the project. If I primarily focus on the fact that my feet are above the last bolt I never climb my hardest and I can't fully enjoy redpointing. "I climb for fun", you might say, "chasing grades is not my thing". Fair enough, just the pleasure of being outdoors, the movement, the sense of adventure - each one on it's own is a great reason to climb (and the list could be much longer). But if you climb for fun, the stress that takes the fun away is even worse for you, because then you are left with nothing.

Fear takes away much more than

sending dream routes. So

many climbers are held back by it, others acknowledge the fact that they get

scared when being high over the bolt or in a strange position and work

on overcoming it. It's

not that bad to be scared of falling or failing, so long as you are

aware of it. It means you can start working on it or consciously decide

you don't want to do certain routes. It seems, however, that there are many climbers

who are terrified of lead climbing without realizing it and this is a

much harder position to be at. They always fail at this nasty crimp just

after clipping a quickdraw. At each bolt there is one of them and the

further up you go from the bolt, the worse the holds become. Until you

are too far away to shout "take" - than it's always possible to get at

least to the next quickdraw and grab it. Anyways, this is what it looks

like watching unknowingly terrified climbers from the ground. They lower down from the third bold completely exhausted, dripping sweat,

breathing fast with eyes fixed on empty space. But the route was two number grades below their limit.

I am currently coming back to sport climbing after a longer period of mainly bouldering indoors, training at home, and a little bit of deep water soloing, so I get scared on a lead, since for me the stress level strongly depends on how much practice I recently had. After a couple of months without tying in it's impossible to push myself on hard moves risking even a safe and relatively short fall. After a few months of lead climbing and when working a project I can skip a bolt and take big whippers. I don't like that I get scared and that I need practice to be comfortable when sport climbing, but I acknowledge it, I acknowledge the fact that I didn't fall because I was pumped or to weak for a move, but because I was scared of falling in an uncontrolled manner. And by acknowledging it I can work to improve that, if I want to. Being honest with myself and knowing why I don't want to do certain things is important. Then, I can make a rational decision whether I want go for it on not.

Dave MacLeod perfectly described this issue in his book "9 out of ten climbers make the same mistakes": It's not this bad for everyone; fear of falling is a continuum from avoiding leading at all costs and climbing feeling like a constant battle, to reckless fearlessness at the other end. For some climbers, it's only a significant limitation to performance in certain situations, such as when very close to their limit, or on certain types of route such as overhanging terrain. In some ways this can be the worst situation, because those climbers rarely realize by themselves they have a real problem with fear of falling. They simply justify their own choices and route preferences, and if climbing partners actually notice this, they are rarely direct enough to suggest that fear of falling is the real force that decides which climbs you try.

Where send?

So you've put the work in, you've trained hard, you've been showing up day in day out, but the project stands strong and you don't see a redpoint on the horizon. If this happens to you, especially recurrently, perhaps you should reconsider you relationship with fear of falling (or your route choices). Of course, climbing is a complex sport and there could be many reasons for not sending your project despite getting stronger fingers (bad tactics is one, particularly in sport climbing). Nonetheless, some kind of fear of falling is a very common reason for not sending, according to Dave MacLeod affecting over 50% of the climbers he's coached (as he wrote in his book, which I recommend to all folks interested in improving at climbing). So if you are struggling on something you don't think should give you that much trouble, you might want to give it a thought. Here is a simple checklist for symptoms of fear of falling (other than the obvious ones, like avoiding leading, or straight up panicking):

- getting suddenly very anxious when

leaving the ground,

- taking forever to try a move that wouldn't be that hard in a bouldering gym,

- feeling mentally exhausted after trying a route several grades below your limit,

- overusing "take!" and "watch me!",

- climbing very slowly and statically, trying to have full control in each position,

- always failing just at the quickdraw (but only after clipping),

- getting surprisingly pumped quickly at lower grades (which indicates over-gripping),

- finding a lot of excuses for why you can't climb a section (except saying that it's scary),

- being fine when trying moves with a lot of rest (hang-dogging), but becoming stressed out when going for a send (this might be also performance anxiety),

- never trying complex moves/positions when higher up.

As I said before, there are many reasons to climb, but if you treat it as a sport and want to improve, there is only one measure of progression - sending harder routes. That is, harder for you, without going down into the grade-discussion black hole. Many motivated climbers fall into the trap of stepping up their training after failing to achieve their goals, while they persistently avoid using this weird high heel hook or positioning their body more horizontally to load that sidepull, all to avoid a fall from a strange position. By the way, the bias towards square-on vertically-aligned-body climbing is a very common error making many routes much harder. You can get only so far with this style. Unfortunate, some would say, but for me the complexity of movement coupled with the strength aspect of climbing is one of the reasons I love this sport so much. So I want to be able to apply it on any route, while having a good fight.

Don't get me wrong, I definitely do not think it's impossible to enjoy climbing without sending routes, of course it is! I've known climbers who are really strong, climb well, and have no fear, but rarely send anything slightly harder for them, because of using far-from-optimal tactics. But they are fine with it! They would fall, pull on the rope to get back where they fell, and immediately start climbing again - they are having too much fun to rest. If you enjoy getting up a piece of rock in your own pace and manner, that's great. Redpointing rules are completely arbitrary anyways. But whatever style you climb in you will enjoy it even more, if you are not scared for the most of the ascent. And if you do like a challenge and you do like to find your physical limit, then getting rid of an irrational fear will put you at a much better position to climb hard (but of course, there is no way around getting stronger, improving your technique, tactics, and other aspects of climbing).

What are we actually afraid of?

Another thing to consider is the real trigger of anxiety when tied into the rope. Climbers talk a lot about fear of falling and everyone have felt it at some point. It's always connected to being high above the ground, but in truth different climbers are uncomfortable with different situations. Dr Rebecca Williams in her book "Climb Smarter: Mental Skills and Techniques for Climbing" defines several types of worries that climbers might experience: fear of heights, fear of falling, fear of not being in control, fear of failing, fear of being watched, fear of fear etc.

If you have climbed with enough people, you've probably seen some of these fear types in action. Do you know a climber who always falls off when everything says they should send? They polished the moves perfectly, the route is not even that close to their limit, they know they can send it without a problem and then they fail. Or they tried a route onsight getting almost to the anchor, it looks like on the second go, already knowing the holds and the moves, they should definitely send it. But they fall at one third of their initial high point. If this pattern repeats itself it could be performance anxiety or fear of failing.

Another climber might go easily through a 7A boulder problem at the beginning of a route, but pumps out higher up in a 6a terrain. When hang dogging it takes forever to rest enough for the next try of a single move at the fifth quickdraw. Or their pace is absurdly slow on a long pitch many grades below their limit. That might be fear of heights mixed with fear of falling.

There are also climbers who struggle when climbing with more people at the crag, especially if they don't know them (fear of being watched). Others are overly careful on the first go, testing every move even at the easiest section, but on the second go they send seemingly with no fear (fear of unknown, fear of not being in control). Or they are masters of tricky heel hooks, deep drop knees, and weird beta in general, when bouldering indoors, but they never use any of it on the rock always trying to have three points of contact (again, fear of not being in control, or fear of unexpected falling).

One can also experience a combination of those symptoms - everyone is different and different people might benefit the most from different approaches. Nevertheless, the first step to improve is to acknowledge the fact that you get scared and decide what to do with it. Even if the conclusion is to simply avoid what scares you (say overhangs, or lead climbing in general), it's much nicer to make a conscious decision about it, rather than being pushed by the instincts, raised heart rate, and sweaty palms.

My experience with lead climbing

I

described a few of the general patterns of fear in climbing, but perhaps

it's easier to understand the idea with a particular example. The only

climber that I know the thoughts and feelings of

is myself, so I will describe my case. I do get scared when lead

climbing and it seems to depend on both - how high above the ground and

how high above the last bolt I am. It is harder to push myself with my feet

above the quickdraw and this is partially rational, since it is easier

to have a bad fall than when having the quickdraw at my hips. But it's

mentally harder even if the fall looks 100% clean. Then, I am more

comfortable with taking, say, a 4 m fall when being at 10 m, than with taking a 4 m fall

what being at 20 m, and this doesn't make any sense. A 4 m fall is much

safer and softer if I fall at 20 m, because there is more rope in the

system to amortize it. There is also lower probability of hitting the

ground, should the last quickdraw fail. Still, even knowing all that it

feels mentally harder to take a whipper at big heights.

I

also get scared when doing any more complex move for the first time on

a given route with a potential for a longer fall. I think it's the main

reason for my onsight grade being quite below my redpoint grade. I should probably

do more onsight climbing... But

just after one go, when knowing what to expect, it becomes much easier.

After one or two sessions I can take bigger whippers on a route I am

projecting, and after a few sessions I can skip a quickdraw (if it's safe). Funnily enough, I feel less comfortable on a top rope

than leading, even

though it's objectively safer, because I don't climb top-rope for a long time now. Practice makes perfect, also when it

comes mental skills.

Fortunately, I don't have any issue with climbing in front of others, nor I get stressed when getting close to redpointing my project. Usually, if I feel I am able send next go I do send. Additionally, I can push myself to try the moves even when I'm a bit scared, after all a little bit of spice makes this sport more interesting. Nonetheless, I prefer to do most of my climbing mentally relaxed while physically trying my hardest and to be in such state I need practice, I need time on the rope (doing moves, not just hanging), and then it just comes naturally with time. Sometimes, I push myself a bit to accelerate the process, I take a few falls, or climb a route that's a bit scary for me. I am lucky in this respect, because fear of falling doesn't deteriorate my enjoyment of climbing most of the time. However, my relationship with this sport improved considerably after acknowledging the fact I do get scared and rationally deciding what to do with it.

I understand that for someone who doesn't climb much the whole idea of being afraid of falling but not fully realizing it might sound like some spiritual mumbo jumbo, but there is a lot going on when lead climbing. You have to think about the movement, the clipping positions, about not putting your leg behind the rope, trying as hard as you can, and about your safety (after many sessions on a project most of this is automatic, but then it's also less scary). It is surprisingly easy to confuse trying a sub-optimal but less scary beta with being too weak for the move, or over-gripping with being not fit enough. I've seen too many climbers defeated by a move that would take them one minute to figure out in a gym lower down and start planning their next hangboard routine... Ok, that's a bit exaggerated, but you get the idea. Maddy Cope explains it nicely in this video. |

| During one of those blissful seasons when falling is enjoyable. Photos by Carlos Navarro. |

When we finally decide to do something

If you know that fear of falling is the main factor stopping you from fully enjoying climbing, there are several things you can do. Personally, I like to first understand a topic in general and see what the professionals have to say about it (professionals in the topic, not necessarily professional climbers). For this I recommend the two books I already mentioned: "Climb Smarter: Mental Skills and Techniques for Climbing" by Dr Rebecca Williams and "9 out of ten climbers make the same mistakes" by Dave MacLeod. The first book is entirely about fears and anxieties common in climbing. Since it's written by a clinical psychologist (and a climber), it goes much deeper into the theory but then also provides many helpful drills and exercises to feel more comfortable on a rope. It is also the only book that cites actual science instead of throwing around a lot of pseudo-science. The second book, although short, is quite broad and contains much more than a discussion of fear of falling, but a significant part of it is dedicated to this issue with useful tips and hard truths provided by one of the most knowledgeable climber.

There are many more books on the topic which from the title sound helpful, but most of those that I have read are not really worth it. For example, "Maximum Climbing: Mental Training for Peak Performance and Optimal Experience" by Eric Hörst and "Mastermind: Mental Training for Climbers" by Jerry Moffatt - although they are beautifully edited, it's hard to distill an actual value from them. Slightly better is "The Rock Warrior's Way: Mental Training for Climbers" by Arno Ilgner, but the analogies to kung fu (or was it karate?) are a bit esoteric and overall too obscure, although it has some useful bits. For some reason many climbing books tend to be weirdly spiritual. They say "Espresso Lessons From The Rock Warrior's Way" by the same author is better. Maybe I should write a book review post...

I would arrange all the advice that I obtained from the books, as well as interviews and podcasts with climbers and coaches, into two categories: things you can do to mitigate the fear of falling in your training, and things you can do to mitigate it when you want to perform. Actually, you could similarly divide improvement methods for any other aspect of climbing. I used to think about the first category as fall practice exclusively, but Rebecca Williams' book changed my mind. Fall practice is definitely important at some point, not only to feel mentally comfortable with it but also to learn how to fall safely. However, going straight to jumping off the wall can worsen the fear for someone who is really terrified. In such cases it's useful to start from something more gentle, like bouncing on the rope. Using mental cues can also help - paying attention to clipping and registering the fact that everything is fine with the bolt and the quickdraw and we are safe to continue climbing. The most common advice is to go only slightly out of your comfort zone each time you climb to build up mental resilience. Then, eventually it is helpful to actually fall off being at least with the hips above the bolt in order to learn how to position the body, absorb the impact on the wall and so on. It is also useful to check the potential falls on a project in a controlled manner before going all in, especially if the fall is weird.

When we already want to perform, that is, we stand below the route we want to send and are about to tie into the rope, there are several things that can help us go to the physical limit without being distracted by fear. First of all, sticking to a known routine. If you bring new climbing shoes and a new harness, and come with a new belayer that you don't know that well using a new belaying device, chances are you are not going to focus solely on smooth execution of the moves. So it's important to keep everything as familiar as possible and minimize unexpected changes to your normal habits. Tom Randall often talks about it and openly admits that for him it makes a big difference, since every little new worry takes away the processing capacity dedicated to climbing.

The second technique to decrease stress when sending a project is to make sure you will be safe while still on the ground. I mean, this is what anyways must be done in order to maintain minimal safety standards in sport climbing. You should know your gear and keep it in a good condition, investigate the route from the ground if you don't know it, and always, always do a partner check (or check everything three times if you are rope-soloing) - that's all essential. But the trick is to really pay attention to the partner check and register the fact that everything is fine. It's about removing this doubt, like when you think whether you closed the door with the key or not. You do it automatically and you have never forgot to do it, but if you don't pay attention and start thinking about it on a bus stop, you might even end up going back home to check. You don't want to be questioning your safety system when getting to the crux, this kind of doubt will not let you climb your best, or will simply make you shout "take". Therefore, you want to have a good look at your belayer's device, at your knot, and think for a moment about the fact that it is all right (if it is right). Then start climbing keeping in mind that you verified everything and you can safely fall off the wall. Similarly, you might find it helpful to register in an analogous way clipping the last quickdraw before a scary part of a route. In general, being attentive and mindful in climbing will result in a more enjoyable and satisfying experience than acting on impulse.

Comments

Post a Comment